Stories - Ceramics and Dead People

Sedef Karayel and Keyla Cavdar are working remotely with torna on their project since July 2025. We are working towards a publication which will be part of the torna Research series.

Below are notes and visuals from their research and progress.

July / Temmuz 2025

I mourn therefore I am, I am—dead with the death of the other, my relation to myself is first of all plunged into mourning, a mourning that is moreover impossible. / Jacques Derrida

Consider the darkness and the great cold. In this vale which resounds with mystery. / Bertold Brecht

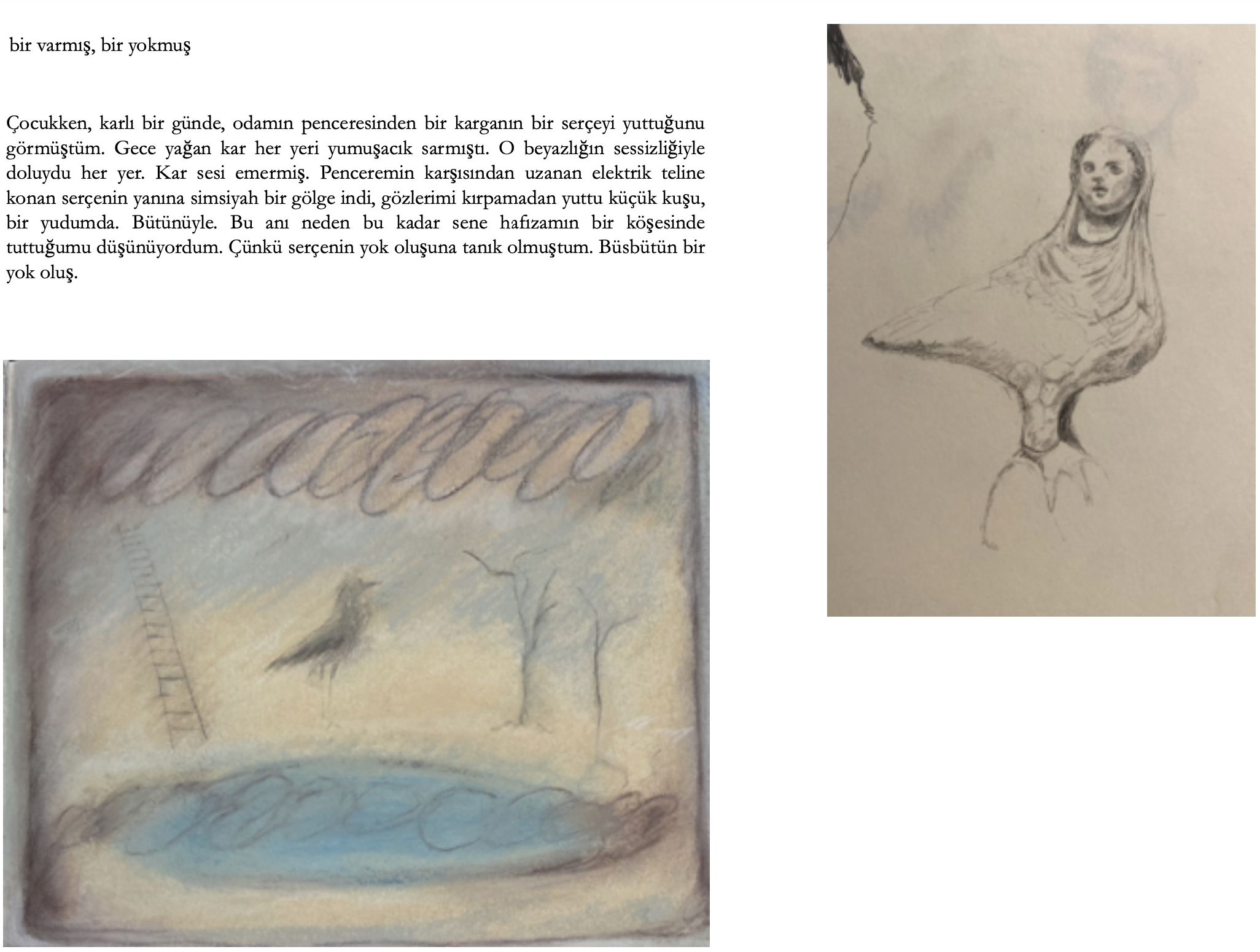

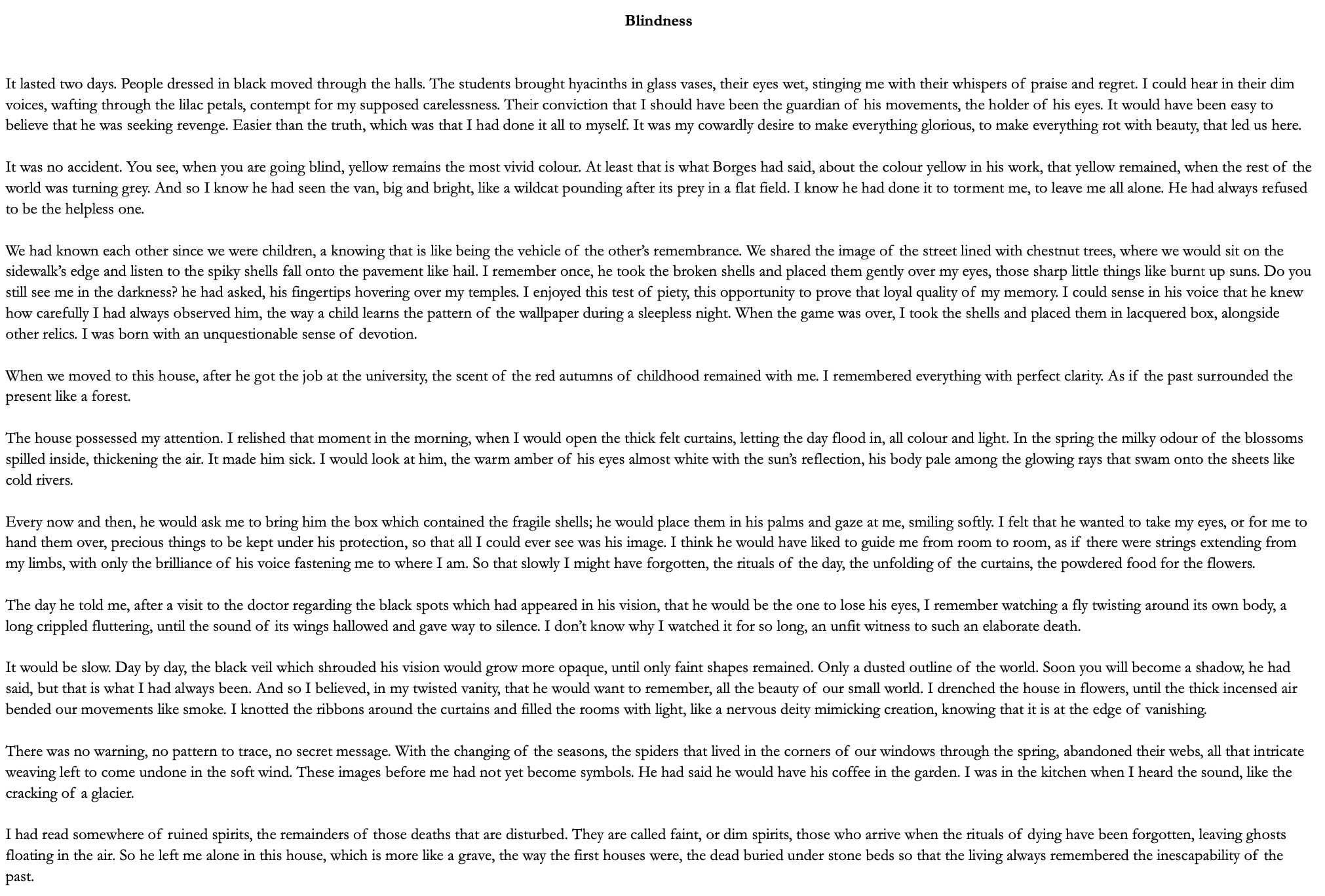

It began with a discussion about graves. We had shared our work with each other, and through this dialogue, seen that both of us were creating from a realm of grief and melancholy. In our families, death always felt hidden. Neither of us had seen the graves of our grandfathers. Yet death was around us.

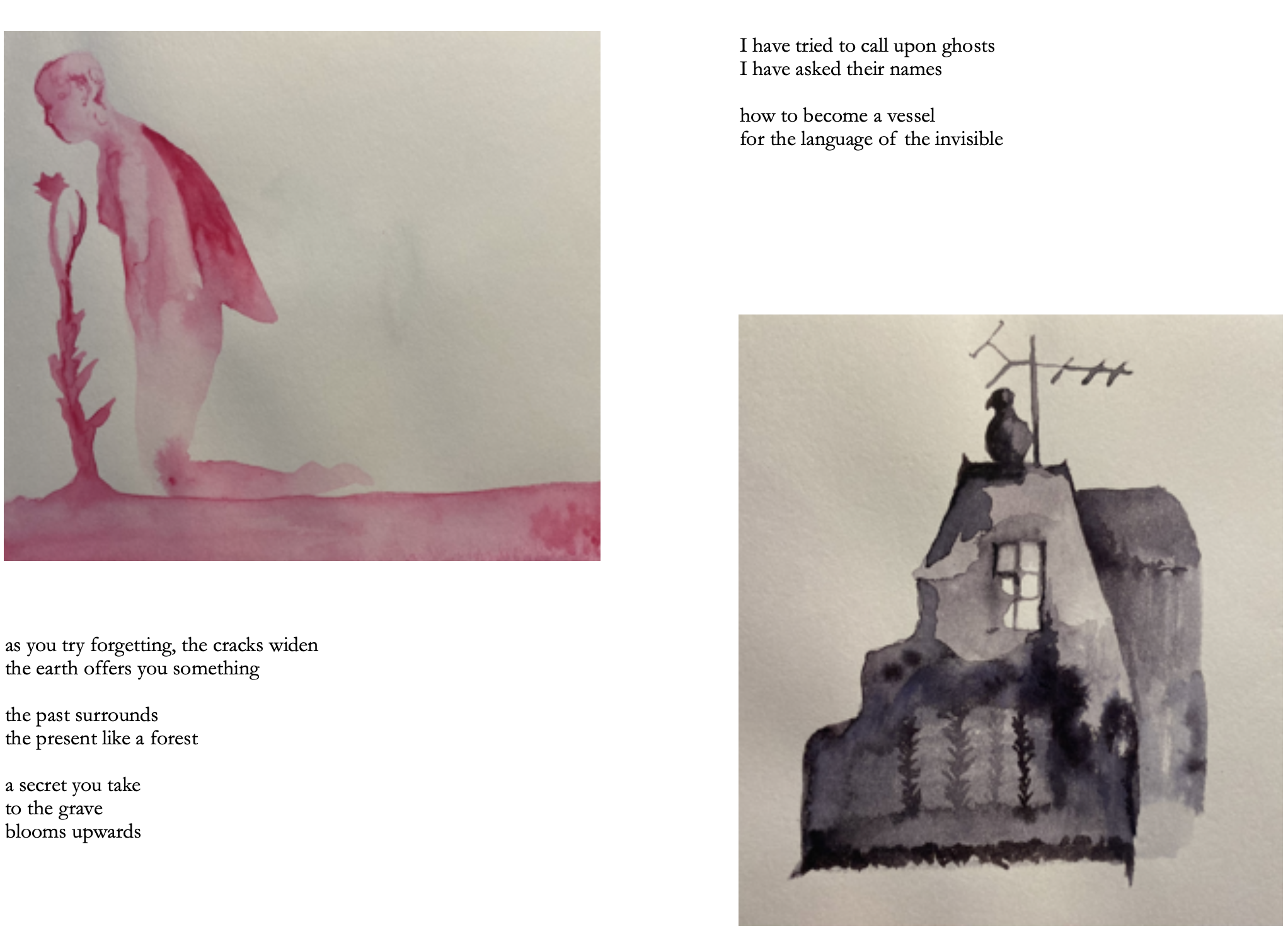

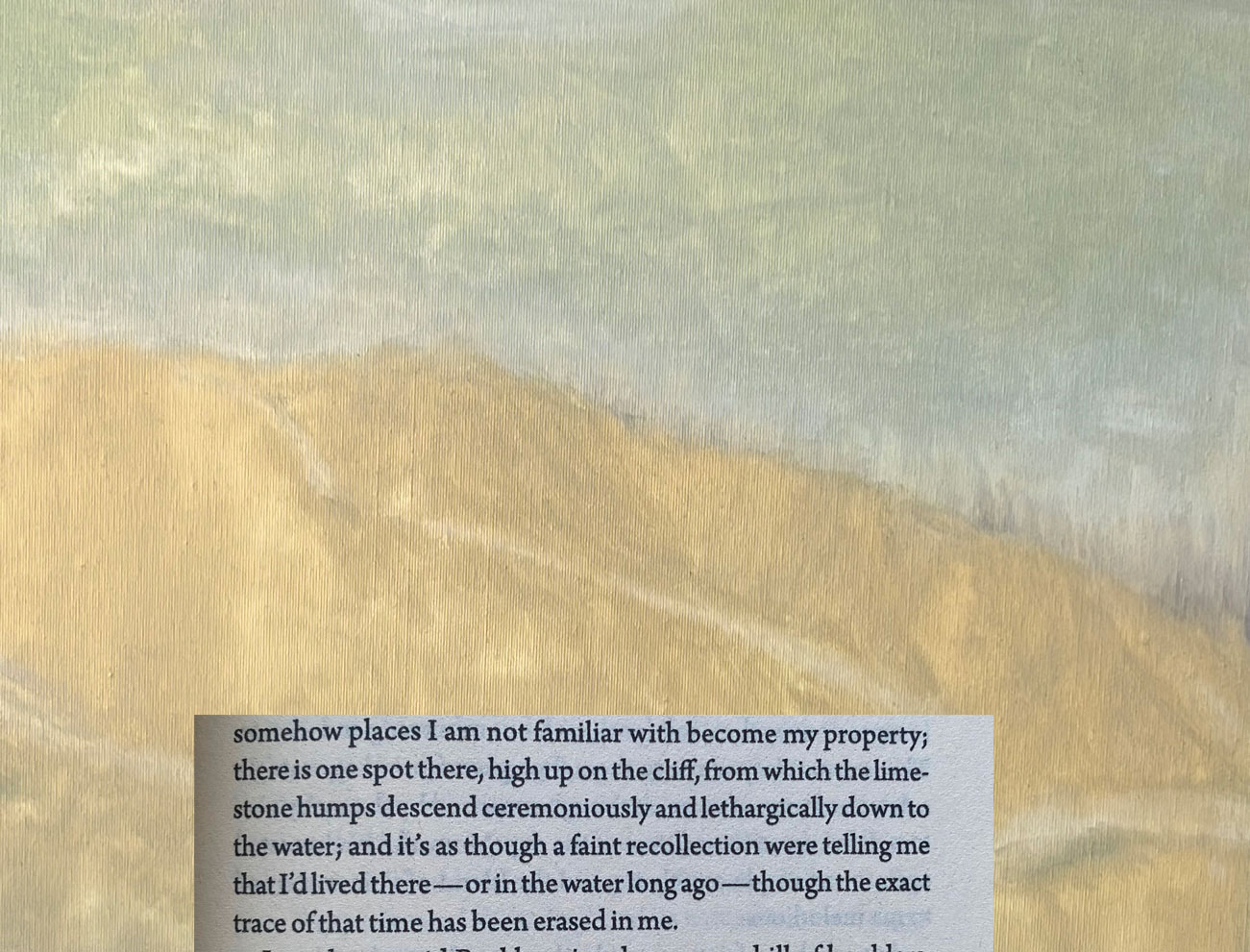

The dead come to us in dreams, in different forms, their voices may call out to us with the wind. Loss inhabits us, like a ghost. Maybe we are trying to come to terms with our dead, trying to find them in the recesses of memory, hear their voices, catch their gaze.It is also our own elusive relationship with loss that we are trying to digest. We began to ask: what is the place from which we are speaking when we speak about grief? It is as if our temporality is inextricably tied to a melancholic consciousness. Does our geography possess a grieving identity? Is this entanglement sprouted from our soil? How does this melancholy, this grief, shape us?

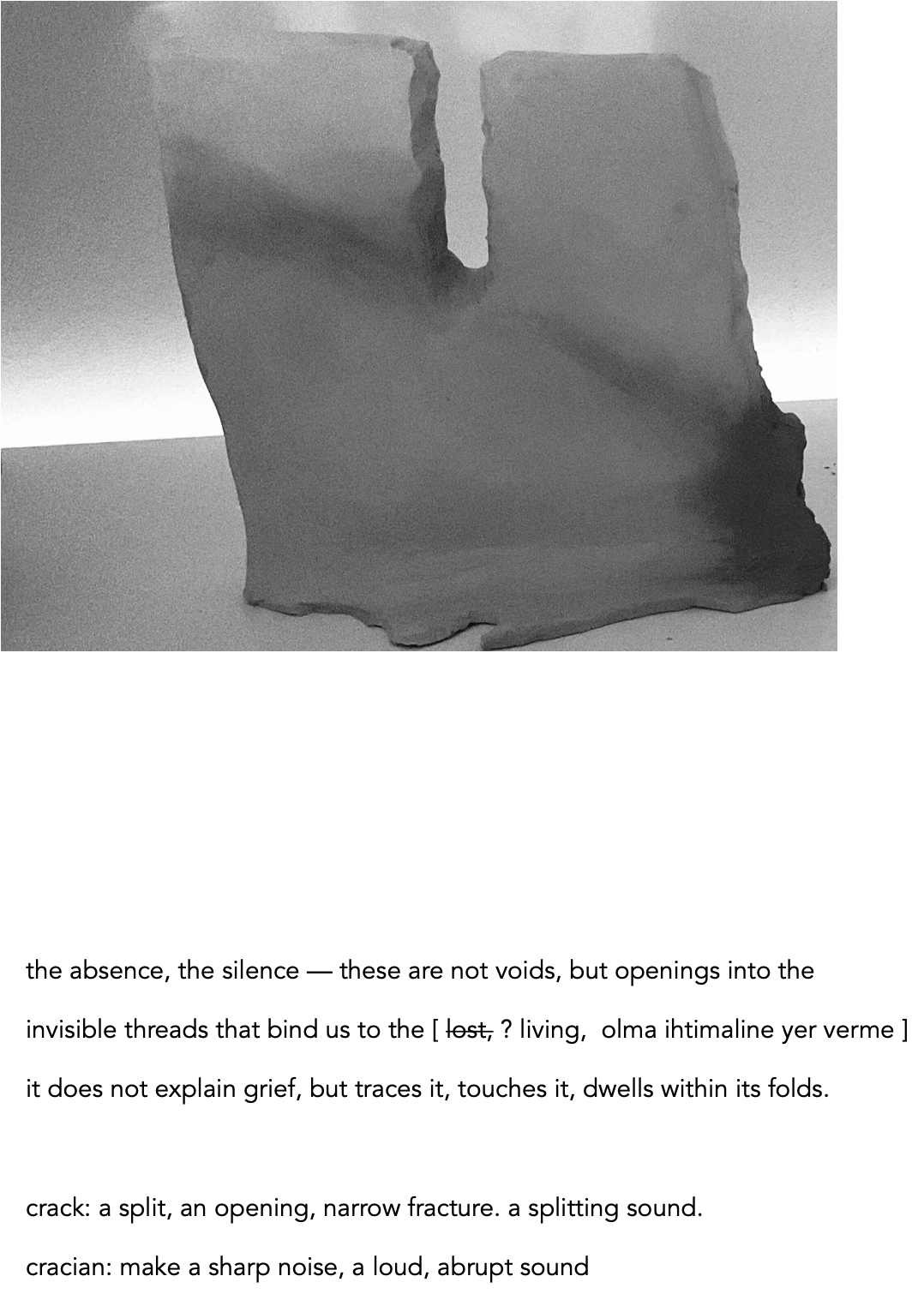

These questions led us to explore the labyrinthine effects of death’s detachment from nature and tradition, its politicization, its transformation into a political action, both on social memory and identity, and on an individual’s relationship with their own life, their own history. These mutations seem to have resulted in the impossibility of ‘mourning rituals’, fracturing the already fragile process of grief and ultimately hindering the creation of an image which holds memory.

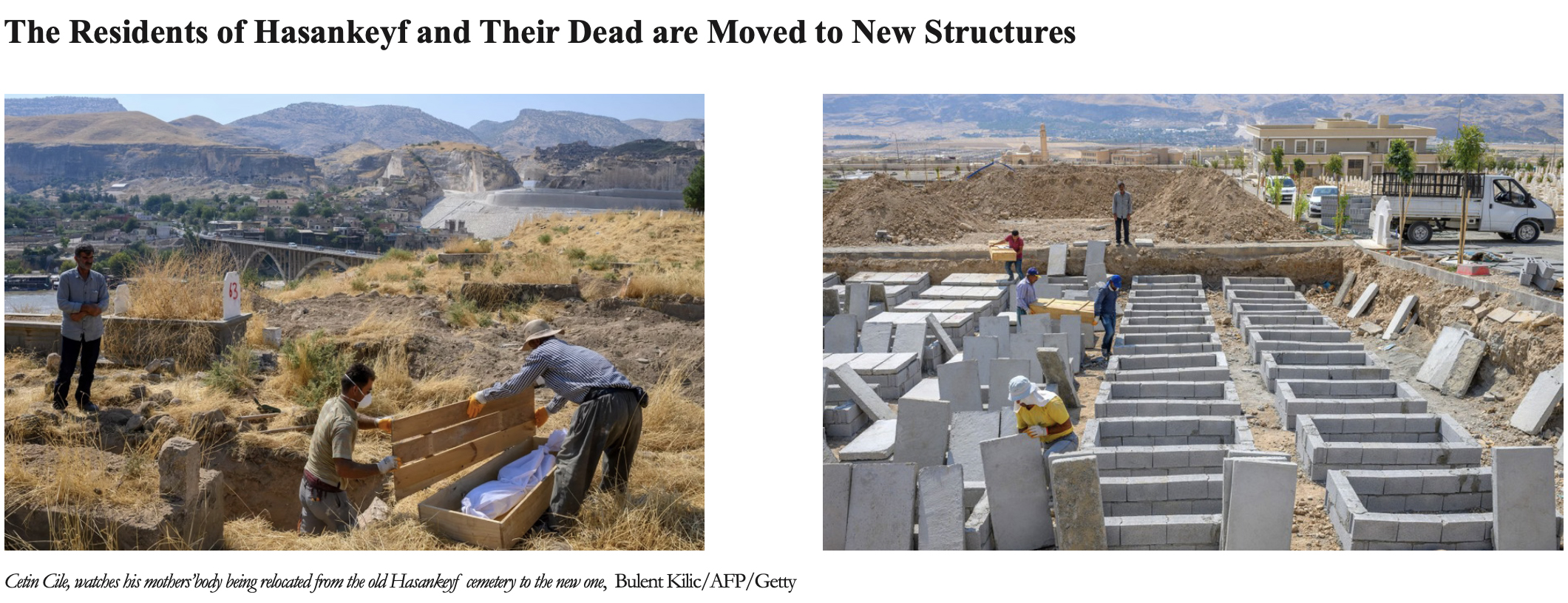

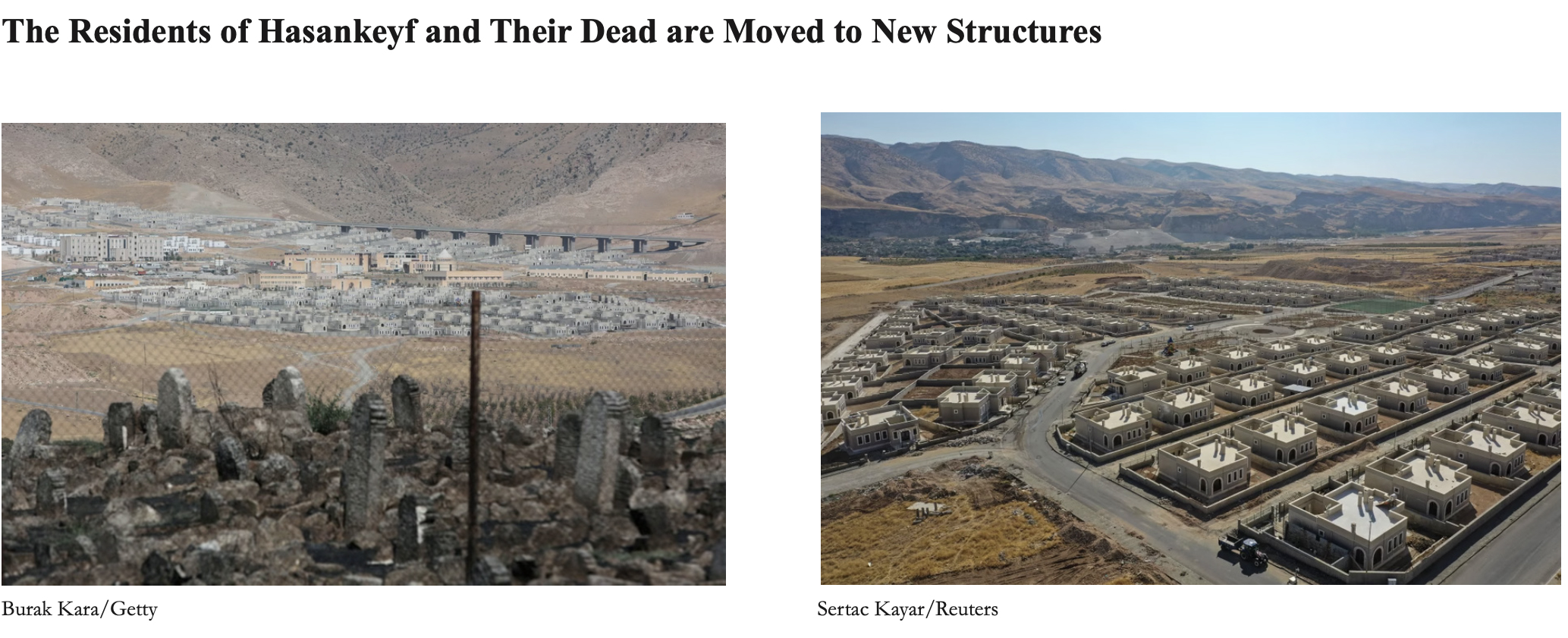

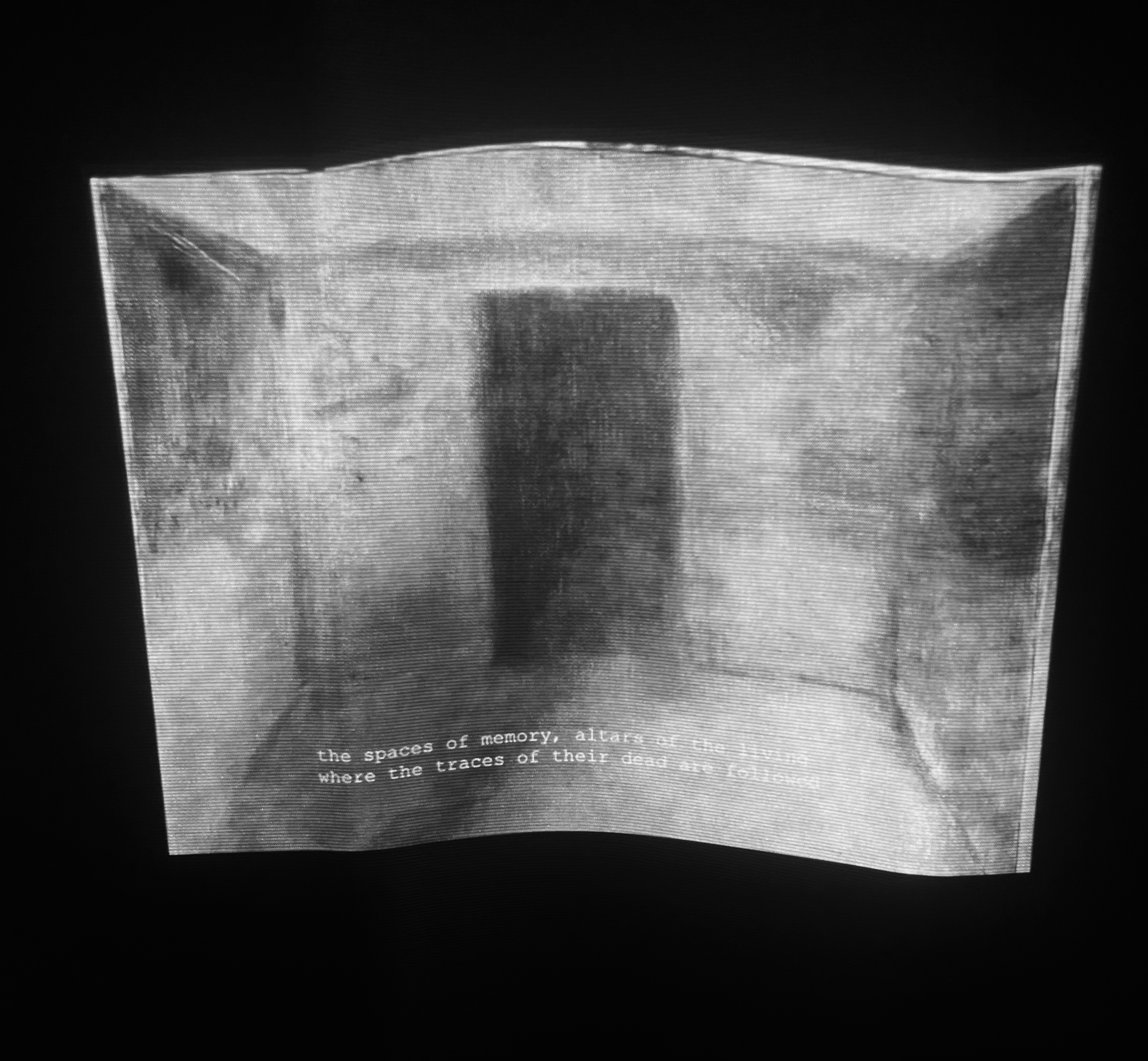

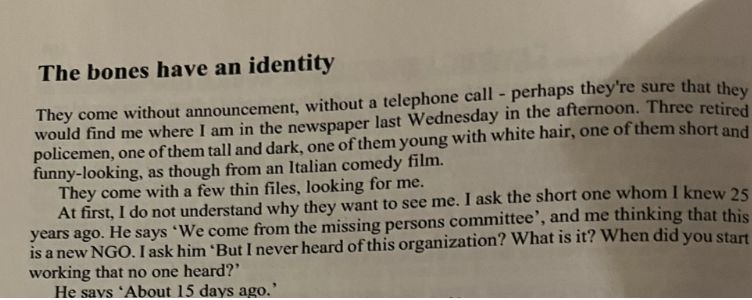

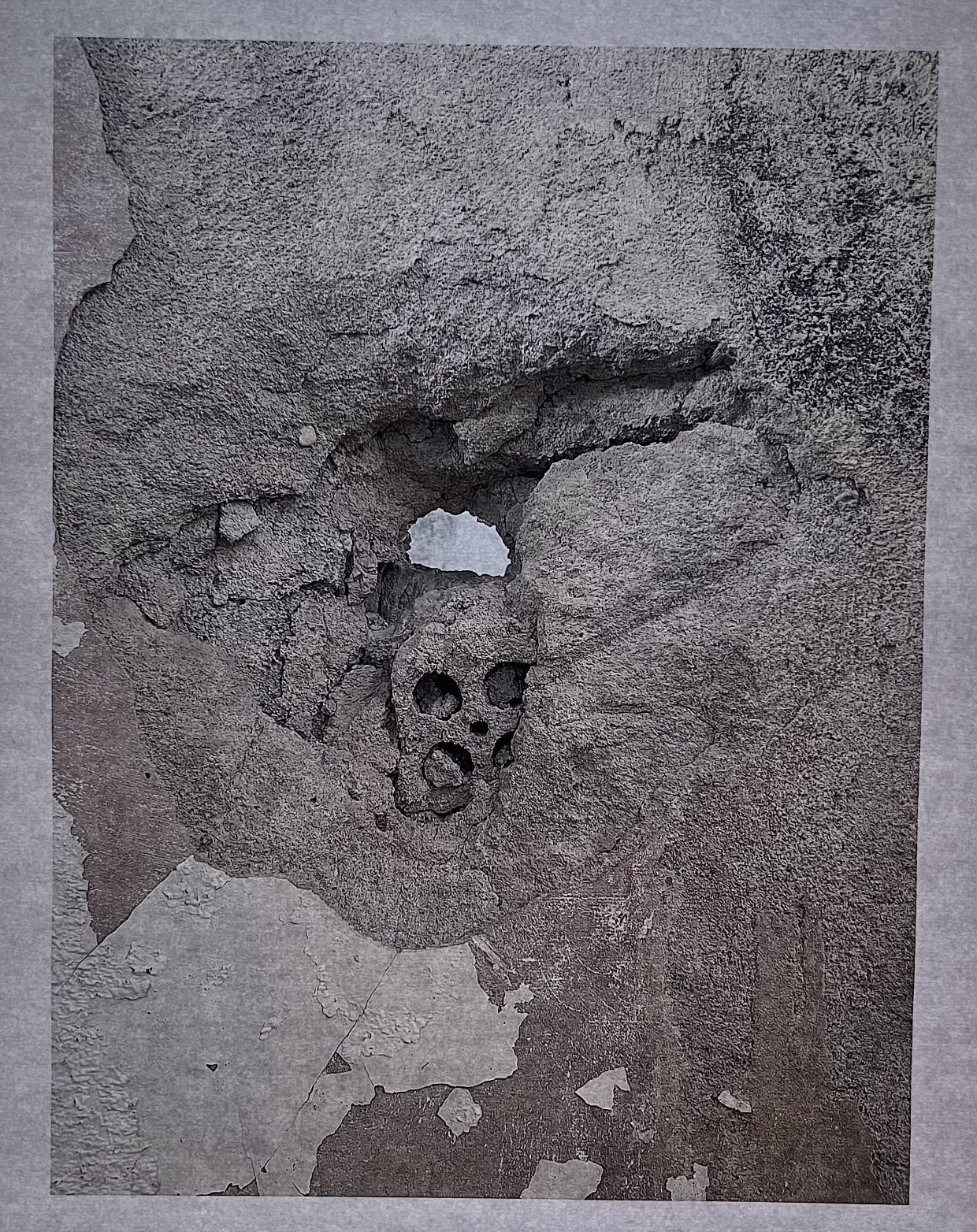

This relation between image and memory brings us back to graves. “Tombstones raise the memory of the deceased who lies beneath… Each grave, each tomb is a small place of worship”, writes Zeynep Sayın in Ölüm Terbiyesi. What happens when we cannot bury our dead, when dying is ridden with haunting? In order to deepen our understanding of the aforementioned experiences, we begin with three stories: Ali Rıza Arslan, whose son was killed during conflicts in Diyarbakır in 2015, receiving his son’s bones in a bag, the almost mythological story of a fig tree leading to the body of Ahmet Cemal who was killed in 1974 in Cyprus and thrown into a cave, and the bodies of the relatives of the residents of the doomed Hasankeyf which were exhumed and reburied before its flooding.

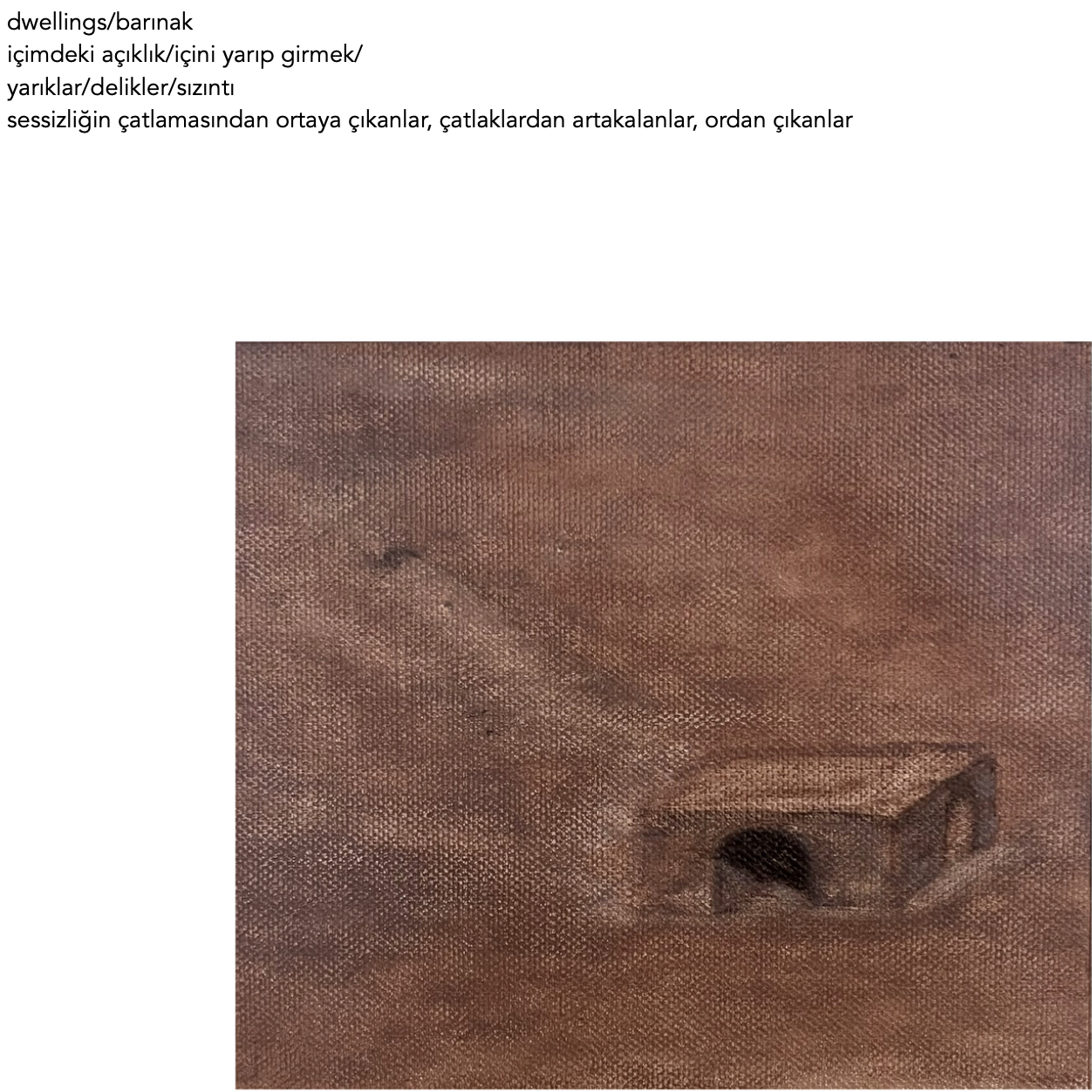

We would like to view this project as a kind of emotional archaeology. Our intention is not to engage with these stories as our materials, but as ‘sites’ in a landscape of grief. In an archeological framework, artefacts, bones, bodies, may be regarded as ‘mute evidence’; they have no ‘voice’ yet are in themselves imbued with meaning, a patient meaning that is in waiting, and it is the task of the living, who act as translators, to decipher their histories. Perhaps we will create a map of this “archaeological site”, a dictionary of its “terms”, an encyclopedia that can be inhabited or dwelled in. Our idea is to materialize, or at least attempt to materialize, the psychic space of grief. The act of creating in and with this notion could also be viewed as participating in, or trying to restore, mourning rituals. A grave is not just a space one goes to visit their dead, it is also a space where one goes to sit with their dead, read next to them, be with them, as if in their house. The state of mourning initiates a kind metamorphosis. The rituals of this life continue, they do not end with mourning, they only take on different forms.

During the residency we intend to produce written work as well as mixed media, and attempt to create an embodied space where the mythologies we are speaking of begin to materialize.

Mourning History

● "Reliving an era is to bring the past to memory. It is to induce actively a tension between the past and the present, between the dead and the living. In this manner, Benjamin’s historical materialist establishes a continuing dialogue with loss and its remains—a flash of emergence, an instant of emergency, and most important a moment of production.” (“Introduction”, Loss: The Politics of Mourning, Ed. David L. Eng & David Kazanjian)

● "İnsanlık tarihi, insanlığın ötekisinin, cesedinin de tarihidir."

● "Mezar taşları, yatmakta olan ölünün hatırasını ayağa kaldırır…Küçük bir tapı yeridir her bir mezar, her bir yatır.” Zeynep Sayın, Ölüm Terbiyesi

● "Establishing ties with my past in the act of mourning—ties that might, in turn, reveal something about me." Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence

It is not there anymore: What is lost

● How do entire lands become graves?

● The earth has always been a grave. And at times it spits back our bones.Or we excavate them. We dig for them, unearth them, disturb the bones of the dead.

• Hasankeyf: ecological-political disturbance forces a relocation of graves

• Wildfires and arson for land capture

• Highways, roads, buildings

Haunting: What remains

● “Haunting is not the same as being exploited, traumatized, or oppressed, although it usually involves these experiences or is produced by them (…) haunting is an animated state in which a repressed or unresolved social violence is making itself known, sometimes very directly, sometimes more obliquely. I used the term haunting to describe those singular yet repetitive instances when home becomes unfamiliar, when your bearings on the world lose direction, when the over-and-done-with comes alive, when what’s been in your blind spot comes into view. Haunting raises spectres, and it alters the experience of being in time, the way we separate the past, the present, and the future. (“Introduction”, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination, Avery F. Gordon)

The kind of community which inhabits that silent coexistence between remnants and routine, become like vessels for the language of the invisible — artefacts, bones, bodies, may be regarded as ‘mute evidence’; they have no voice, yet are in themselves imbued with meaning, a patient meaning that is in waiting, and it is the task of the living, who act as translators, to develop a language with the invisible. We would like to view this project as a form of “emotional archeology” where different forms of loss can serve as sites of excavation.

Embodied Time - the function of the body in memory

● living body becomes the guardian of the past

● Merleau-Ponty, in his notes, insists that ‘the body [is] an apparatus not only perceiving space, but also time’. he also adds that ‘memory of the body’ is capable of evoking our past more that our mind can-is focused on the role of forgetfulness.

September / Eylül 2025