torna conversations #3 (Part One)

with Charlie Coffey

See Charlie's online project here.

---

MERVE KAPTAN: You are quite a private person. You are also British, which secretly forbids you from being too outspoken; teaches you to be polite, conscious and greedy (if needed) with your words.

CHARLIE COFFEY: Ha ha, oh dear, the first of these questions is way more personal than I’d expected!

Well it might not surprise you to know that both my parents went to boarding schools in the late 1940s - 50s and both my grandfathers were vicars. I also grew up on a string of different army bases as a kid. So I think questions around Britishness, British institutions and what you might call the wider establishment feel quite close to me and how I was raised, which inevitably finds its way into work and life.

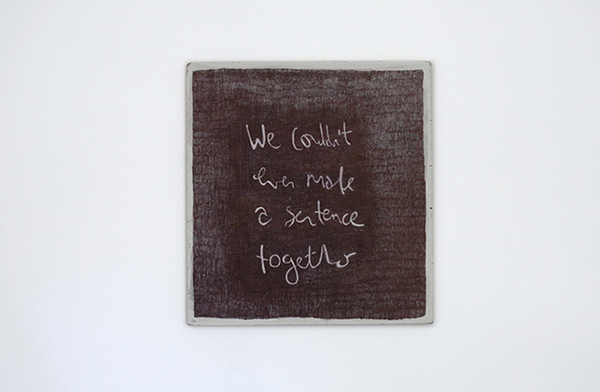

Maybe what’s interesting is whether those - what you’ve called British - qualities are contained within my work somehow or how I approach making work. I think of drawing – maybe my principal way of making work - as quite an introverted activity, which is probably quite common, though obviously it can be more collaborative. I still spend hours making labour intensive drawings, for example. And without wanting to romanticise it, it’s stupidly frustrating at times, maybe there’s a certain sensibility around quietness in my drawings - or politeness and conscientiousness in your words. This is both in their solitary production and the way they seem to speak to the viewer...for example, I don’t think I’ve ever made a shouty drawing. They tend to be quite intimate in scale and the text often invites you to look more closely or come into the work's personal space, if it were a person. I'm interested in how distance effects the viewer's interaction with the work.

Another thing - drawing is like a first response to an idea, a way of sketching out something before it develops further, but conversely at the same time it feels like a conclusion. It can also have that kind of finality about it.

MK: Why do you draw words?

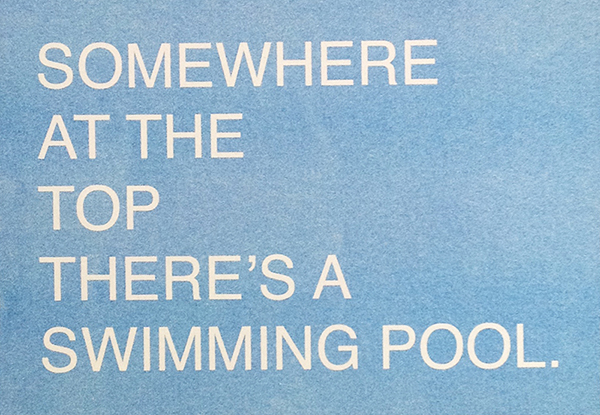

CC: I’ve drawn words for a long time now, it's been a persistent, though not always dominant, thread within my work. I seem to find myself time and time again pulled back into working with different modes of public display or distribution of ideas/information, like the billboard, street sign, leaflet, map or poster. Maybe these are all platforms that allow the visual possibilities of language and words to come through. They’re also about communication and the communication of a certain message.

To go back to drawing text, I think there’s something about handwritten words, the way they seem like representations of words or suggestions for printed texts, as if they’re in a preparatory state or reveal an underlying structure/process. That's why an unfinished drawing is always the most interesting kind of drawing for me. And like a lot of other artists, I’m interested in what happens when you take excerpts of text from their original context and position them elsewhere, which I’ve been doing more and more with print and other forms recently, as well as drawing.

MK: I agree. You already take advantage of that misplacement when words are used in any form or context. A word will always have to live in that 'misplaced' zone whenever the artist re/uses it, whether in written or spoken format.

C: There is something antagonistic about it almost.

MK: 'It's A Girl!, Light industry Projects'. This is the title of one of your works and the location it takes place. You added this on your cv as a past project, but there wasn't actually a 'real' show as such. Tell me about it.

CC: So this work was a clear, single-minded attempt to document or record time taken out of an art practice as a result of having a child. It came out of frustration that I couldn’t do as much as I wanted; there were too many, and still are, constraints to work within. All that stuff about the pram in the hallway (“there is no more sombre enemy of good art than the pram in the hallway” writer Cyril Connolly) is narrow minded and strangely child-disliking but true in the most practical sense that the external world; the visual arts world and (early years) childcare provision, let's say, don’t lend themselves well to sustaining an art practice. Words like invisibility and exclusion come to mind. So the piece was a tiny little defiant gesture, but not one I mentioned to anyone else but you at the time, that felt right in its own way…just to record that absence from being able to continue.

You might ask why I chose to represent it as an exhibition on a cv, I really liked that this could stand in as a simple, indivisible unit of measurement. That the time out of making work could be marked using terms that are universally understood and, to throw a provocative little statement in there, considered worthwhile.

I think there’s also a more general disinterest in the how parenting intersects with work by those who aren’t affected by it (an issue for all parents, not just artist parents) and pretty sadly, something that seems to characterise a lot of feminist issues. But I never really wanted to make work that’s substantively about parenting, childcare or any of those related experiences, I just wanted to address this political dimension in a small personal way.

And It’s A Girl! was just a little reference that was funny to me at the time, a crap joke about the (I could say pretty much outmoded, but that's not entirely true) gendered way of celebrating a child’s birth. It felt quite appropriate somehow because of everything I’ve just described.

MK: In the past, we've spoken a lot about the 'ruin value'. For your next project you said you were interested in working with an architect who would imagine the construction and the ruination of a building, as you put it 'the future ruination' imagined by the architect.

CC: Yes that’s right, an architect or architectural illustrator. This comes from working in a John Soane building for some time now, where I’ve become slowly, unwillingly entrenched in the world of this eccentric English neo-classical architect. It’s important to draw the distinction between ruin value, which was a concept dreamed up by Albert Speer, the lead architect of the Third Reich, and a pre-existing romantic fascination with ruins that it built upon in the work of people like Soane. He worked with a long-time collaborator, Joseph Gandy, to illustrate his architectural designs and sometimes also their future ruination, rotting in the ground. I think the most famous example is his commission for the Bank of England, where Gandy produced drawings of the building a thousand years later in ruins. Soane first encountered this European tradition as a young man on the grand tour in Italy, where he came across Piranesi’s intoxicatingly beautiful, haunting illustrations of Roman ruins.

MK: Are Soane's motives really that different from Albert Speer's ideas? That idea of control is crazy.

CC: No I don’t think so at their core but they were put to very different uses. Speer's fed into the whole Nazi nation building enterprise (associating the Third Reich with great empires of the past), whereas Soane’s was a personal interest that was about securing his own professional legacy. His motives weren't wrapped up in an ideology of disastrous scale and human consequences. It was about furthering his own architectural reputation in perpetuity, the fantasy of a self-made man who hadn't forgotten his humble background despite his considerable success. Imagine if you could wander the Bank of England ruins now in the old city of London around all those faceless glass towers that have gone up, although it's only 200 odd years since the drawing (Soane's prediction of 1,000 years).

I guess what struck me was the idea of ruin value itself (the Soanian, pre-fascistic version), a kind of incredulity that any creator would seriously pursue the ruination or degradation of their own work in this way. Like you say, that level of control is crazy. Also the idea that you’d consider the future lineage of your work to be an ongoing concern, as opposed to something which passes over responsibility to whoever it belongs to. In art anyway, there isn’t really a sense of ownership over your own works once they’re gone to another party. Not that that’s particularly relevant, it’s a pretty different field.

This discussion is pretty focused though, a lot of artists are interested in ruins and a lot’s been said and written on the subject recently. Particularly on the passage of time and why humans continue to fetishise the ruin, and what it is about this particular point in time that gives them an enduring appeal. All of which can be said a lot better in this quote from Jonathan Moses (!) “We find ruins sublime because they overpower us with the sorts of relationship denied in the corporate landscape: a melancholic hyperawareness of time, through which we are quietly confronted with death” (OpenDemocracy, 2013).

MK: During the current political violence in the world, I find the ruin - noble or not, even more interesting. Right now it is incomprehensible for me to imagine some of the Western giant structures like the Houses of Parliament collapsing and turning into ruins. The ruination and disaster processes seem to be so familiar with other geographies. The idea of ruin does not always bring the idea of control and romantic sublime in mind but destruction and surrender.

If you were to draw the Houses of Parliament in ruins now, it would represent one of the greatest defeats of our time, not a romantic glory. I guess it would be the same for places like the Colosseum in Rome. Right now we look at it Soane's way, admiring the great powers that ruled it once, but if we were to imagine it in ruins at its peak times, it'd be disastrous and not politically correct.

CC: Yeah, to imagine something in ruination during its very peak is something different. To draw the ruins of something still standing now, especially a building of such great standing, would be highly antagonistic. I was interested in that even though I felt it had the potential to become a gimmick.

It's funny you mention the Houses of Parliament because those buildings are actually in a pretty bad way, there's ongoing discussion about where MPs should be relocated during the eventual restoration. But I'm not sure how much we should compare these two types of ruins; artificial ruins or those created with an aesthetically pleasing demise in mind, with the devastating ruins caused by war or natural disaster. We're able to fetishise the classical ruin because the cause of its ruination is so remote from us. The long stretch of time mitigates past suffering in a way that’s not true of today's ruins you're thinking of. Effectively there's an absence of destruction, instead it fetishises the aesthetic of destruction.

But I'm interested in ruins for a number of reasons – how classicism is a byword for architectural conservatism, a signifier of a certain attitude, this fetishisation of the ruin (not only classical but post-industrial) and the sort of adolescent boredom of being taken to see a ruin (which somehow seems to relate to that cliched idea/phrase the weight of history). Then there’s the ruination of ruins, thinking of places like Palmyra.

MK: Where do you place Palmyra in this? The destruction there declared our modern relationship with the ruins; to me the attackers did something very powerful and very strange. The destruction of Iraqi history and centuries old artefacts during the last war didn't hurt the world as much as what happened in Palmyra, when some weird men in masks with massive sledgehammers filmed themselves destroying things one can't bring oneself even to touch.

CC: I don't associate Palmyra with ruin value particularly, but as a significant cultural event. I see your frustration with the hypocracy in the western press but I’m not sure whether unbalanced coverage of world events makes the destruction in Palmyra less meaningful? It was a very powerful action by the attackers, you’re right; those videos are unforgettable, painful to watch. We respond exactly as we’re intended to in a deliberate attempt to shock. There’s also a kind of hyper-masculinity there. And perhaps controversially, if you’ve ever deliberately destroyed a physical object or something that’s not yours, you’d know how exhilarating that experience is. I wonder if the knowledge of this comes into play at all, a kind of sublime terror, combined with our shock at the barbaric erasure of something so precious, so irretrievable.

I read somewhere that these were “viewer-friendly” atrocities, ideal publicity because they’re so suitable for online sharing (in a world where beheadings are unpalatable to most). There’s a well-reported media savviness about ISL/Daesh’s videos – or media output I should say. They appropriate the content and visual language of Hollywood film in a way we feel we’ve seen before. We’ve all read Baudrillard talk about ideas relating to this, and on September 11th and the 1st Gulf War.

But I’m not sure what our modern relationship to ruins is after all this – it's very complicated to untangle. Do the videos prompt a renewed fetishisation of ancient ruins? I think it may be more sobering, it feels like there’s little romanticism there in the extinction of these forms.

MK: What will you ask your architect to draw?

What I want to do is a small gesture really. It concerns the use of ruination as a tactic, an undermining tactic even in the way that we touched on before. I wanted to envisage the ruination of one of Soane’s buildings, in fact the one I work in called Pitzhanger Manor, and to specifically do this as it begins a three year redevelopment. It was this idea of twinning the two opposite trajectories, imagining the place as a languishing ruin as it stutters forward towards its newly restored, reopening to the public as an archetypal, user friendly 21st century cultural site. For me it was important to do this with someone I could commission in the way Soane collaborated with Gandy.

MK: Give me a list of words that describe things that bother and interest you.

CC:-Politics with a capital P

-Society, social structures, power structures that govern our lives (governmental/supra-governmental)

-Ways out (utopias – historical, linguistic and literary)

-Islands (escapism, symbolism)

-Communities and community engagement (how the community interacts with wider structures)

-Alternative, collaborative living and working models.

-Ideology, the way it is embedded in the visual, material world around us

-Public and private space (workplace and leisure space) / how this connects with the built environment

-The luxury industry

-Tourism

-Unfailingly, the social impact of art

-The agency of the artist - why anyone bothers to keep on trying (I read this article many times last year: http://www.spikeartmagazine.com/en/articles/qa-nik-kosmas)

-Happiness – which somehow seems to relate them all.

(and the many connections in between)

MK: So why do we bother keep on trying?

CC: That's a question I return to often enough! I guess the simple answer is that it's inconceivable not to, which is kind of interesting to break down. Almost funny because it feeds into that romantic notion of the struggling artist genius. But I think a lot of artists are bound by this way of thinking, there's a hidden pressure to keep going and it’s pretty unfashionable to talk about why you might not want to make art any more (why that article by Nik Cosmas in Spike magazine was interesting, I thought). It highlighted some of the unspoken things about making art and being part of the art world that really bother me. But that isn’t the most encouraging answer to your question, sorry!

Charlie was commissioned to produce an online project for torna.

We also published a print version of the project. See it HERE.